If you are reading this, you have probably heard of the safety net. I’m not talking about an actual net, like one you might see at a high wire performance, but a figurative one. A net made up of rules, policies, and regulations and administered by volunteers, civic groups, government agencies, religious congregations, and non-profit organizations.

It’s a net that protects you and your fellow citizens. You may not know exactly what the net is or what it does, but you are reasonably certain that it exists. You may have never needed it and believe it only exists to help others, but you hope it will be there for you if you do need it.

People disagree about the safety net. Some people believe that the safety net is larger than it needs to be. For others, it is too small. Some argue that it doesn’t really exist, at least not in certain geographic areas or in certain sectors of our economy.

Writers and artists have often depicted a physical safety net to assist our understanding of what a safety net is and why we might want one. We call this use of symbolism and story to define an abstract concept an allegory.

This is one explanation of how a Safety Net Allegory could work and how we could use it to help explain how a safety net supports our economy.

Unlike stories which are printed and bound, this allegory is shared virtually on the Internet, which allows the author to write and rewrite the story to make the allegory work. You are, therefore, not reading the first or final version of this story, but rather the most recent, and with hope, the best.

Start

Every story has a beginning. Ours is no different. It begins with a person getting ready to step out onto a wire. We’ll call this starting point, Start.

For a high wire performance artist, the goal is to move forward from a starting point towards a desired destination marked by the end of the wire. The higher the wire is, the greater the risk and the greater the reward, if only in acclaim. The high wire artist has many different places he/she can perform his/her act. The only differences are the height and the length of the wire

Our economy has similarities with the high wire performance act. Like the high wire artist, there are different starting points and destinations depending upon what is being purchased. There is a similar goal, to move forward to reach a destination. We call this movement economic activity. And we call the people that participate in that activity, agents.

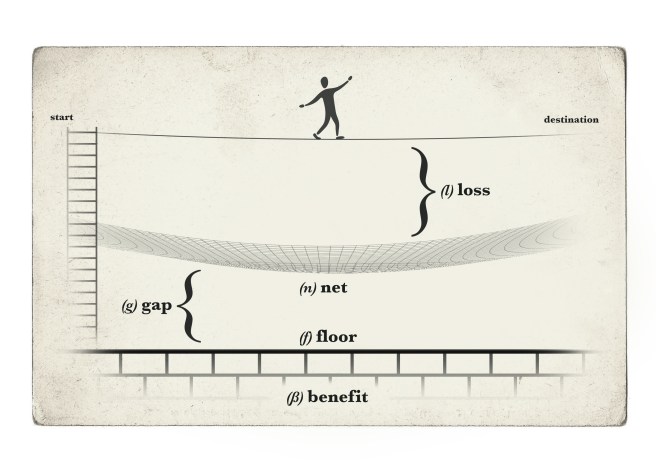

So, this is how our Safety Net Allegory begins – with our agent engaging in economic activity by taking the first and continuing steps on a wire from a starting point towards a desired destination (see Figure 1).

The desired destination could be an intangible goal like a career or a material object like a car or a home. Some destinations come with greater risk and rewards than others. However, the route and destination aren’t as important as the fact that our destination requires movement or action for the goal to be obtained.

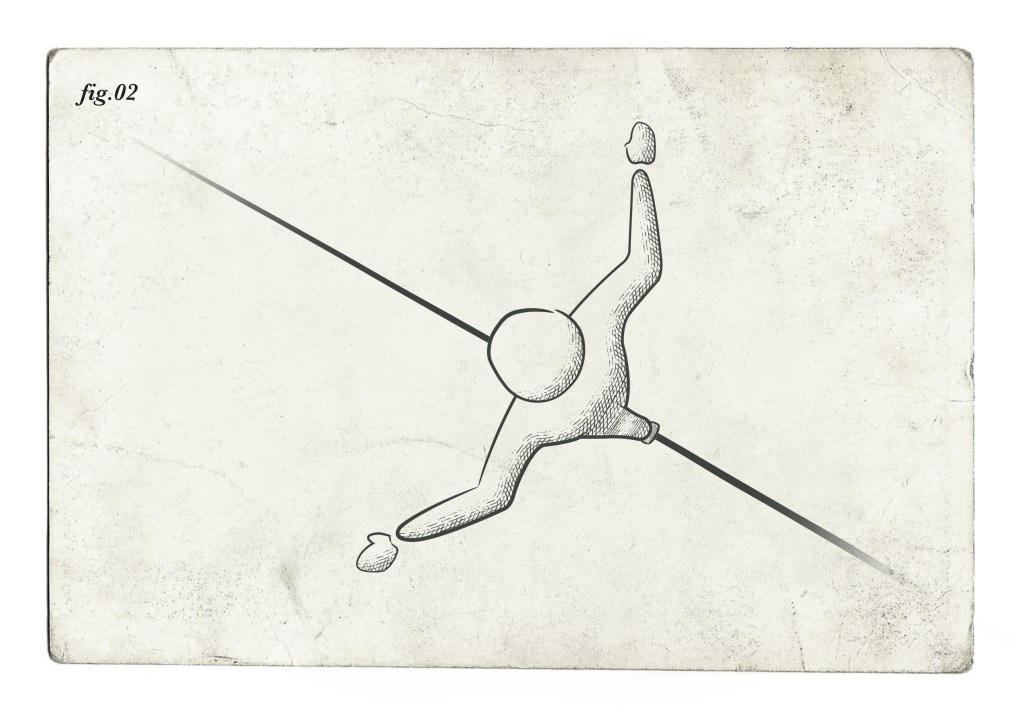

In our economy, we don’t want our agents to stand still or go backwards. Standing still could lead to a recession, or worse, a depression. Similarly, in our allegory, we don’t want our agent to remain at Start, to stop (see Figure 2), or to move backwards along the wire.

We need our agent to move forward.

But with movement comes risk. An agent, like the high-wire artist, can fall from the wire at any point. Success is not guaranteed.

Risk is a problem in an economy. Risk means a potential loss of something of value. To most agents, loss is something to avoid.

What a loss could be depends upon the activity in which our agent is engaged. For a delivery driver who wants to take on a new customer, a loss could be a single package or an entire shipment. For a network engineer who wants to update their system, a loss could be one file or an entire network. For some agents, the loss is simply the time spent engaging in an unsuccessful attempt.

Agents generally like to avoid loss so they either avoid or try to minimize their risk. Although some agents are more comfortable with risk than others, only a few agents, probably not enough to maintain our economy, will engage in an activity regardless of the risk. Even fewer agents will act if what they could lose is unknown. Even when a loss is known, it could be unacceptable or even just unappealing, and as such, could inhibit engagement in an activity that our economy deems important.

In our economy, there are entire segments created and maintained to reduce risk and loss. So, for our Safety Net Allegory to work, it also needs to take into account the risk of loss and a way to limit it. For our delivery driver, one way to reduce a potential loss would be to purchase insurance. For our network engineer, it may be to have redundant or backup systems.

For a high wire artist, it could be a net (see Figure 3).

The Safety Net

Our economy is based on several accepted premises – one of which is that our agents should desire or need things, both tangible and intangible. What the thing is isn’t really important as much as it is the desire to acquire it. It is that desire that keeps our agents moving towards their respective destinations. Our economy needs movement. So, to encourage our agents to move along our allegorical high wire towards their allegorical destinations, we could put in an allegorical net.

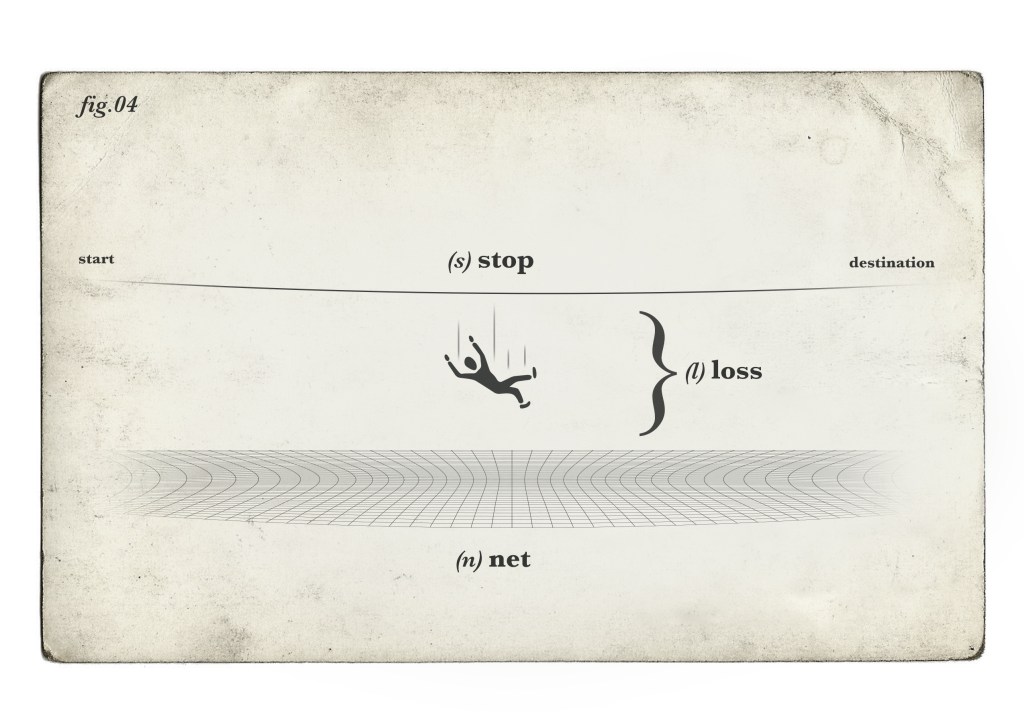

In addition to creating a way to prevent or limit the loss, our safety net, and the allegory in which it resides, does three things very well on a visual scale (see Figure 4).

- First, it fixes the point at which our agent stops engaging in an activity. We’ll call it stop (s).

- Second, it helps the reader visualize and measure loss. We’ll call it (l), which is defined as the space between the wire and (s); and

- Third, it shows how a net (n), can limit loss and as such, encourage economic activity.

Perfect. Net installed. Loss measured and limited. Problem solved. Our allegory is complete. Or is it?

The Problem with Safety Nets

Encouraging Activity and Guaranteeing Outcomes

A net doesn’t completely solve the problem caused when an agent stops and falls. First of all, our agent is caught in the net. She hasn’t moved forward. In, fact, she isn’t going anywhere. In our allegory, our agent cannot climb the net to reach a destination. She must use the wire.

Mind you, she hasn’t hit bottom, which is good. But, depending upon where the net is set, the net may not get our agent back on the wire towards her destination. It just catches her at a point where she will remain until she decides to give up or start over and lower herself to the ground.

If we want our agent to get right back on the path (in our allegory, the wire) to her destination, we will have to do something more with our net. Something that isn’t possible with real nets, where the laws of physics apply.

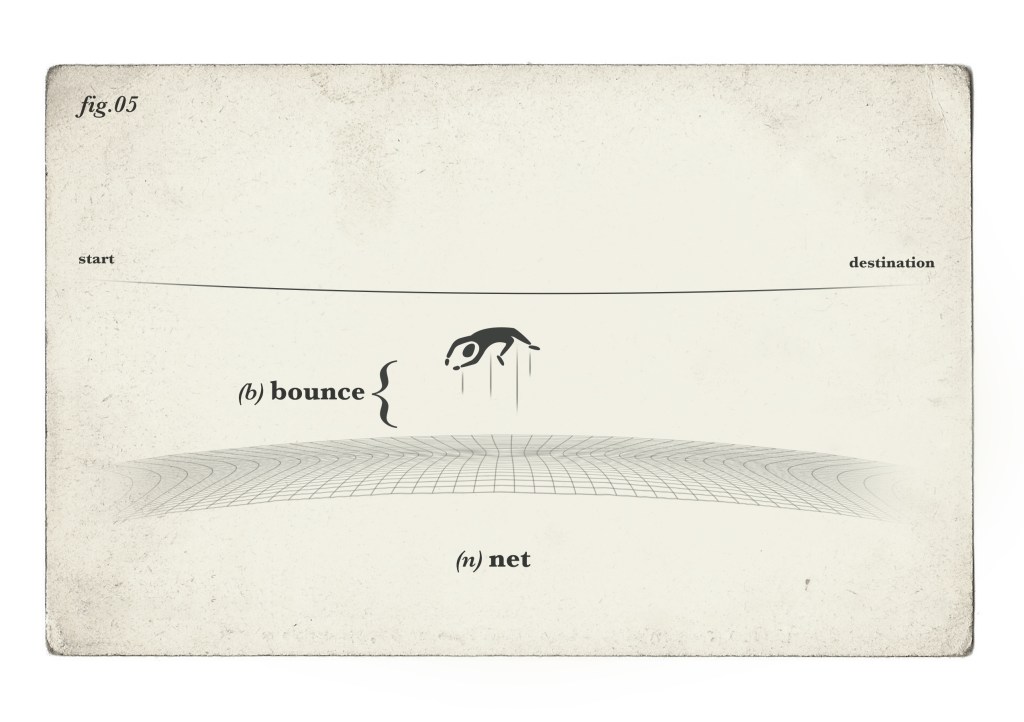

In most cases, if you fall into a net, the net just catches you. However, in our allegory, if the net has enough tension, you can bounce up off the net like a trampoline, if only slightly. We call this tension calculation (b) for bounce (see Figure 5).

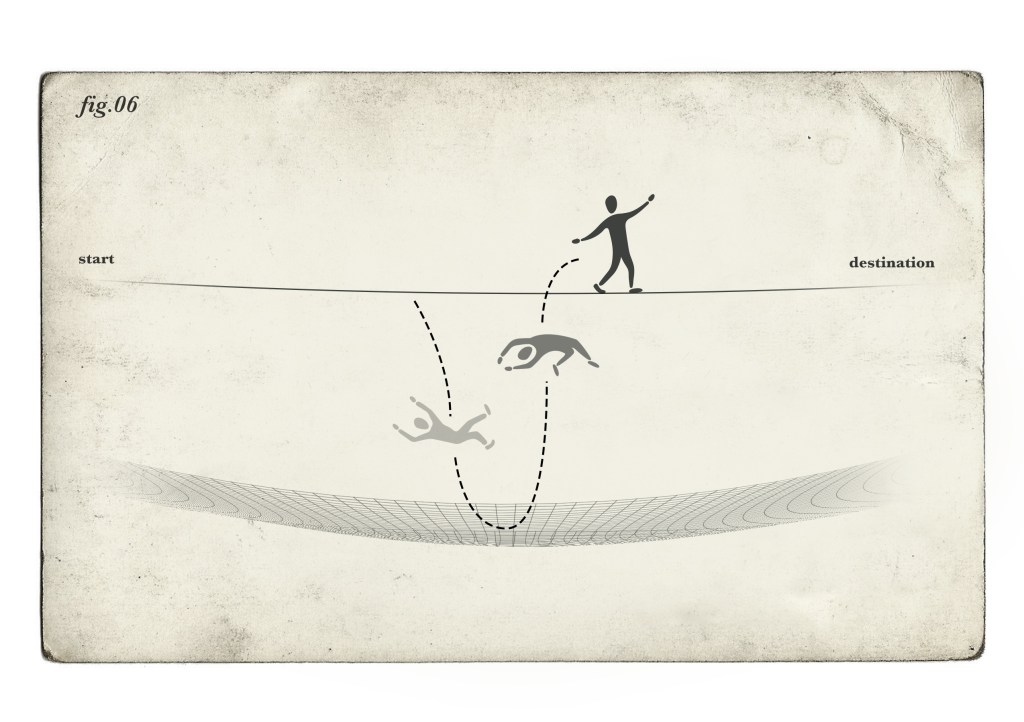

Even better, in our allegory, if you put our net at just the right height and tighten the net to just the right tension, our agent can fall, bounce on the net, and return to the wire (see Figure 6).

So, in our allegory, bounce is important. While the net can minimize loss, the advantage of bounce is that, if we want it to, it can bestow our agent one or more attempts quickly by returning her to her stopping point (s). Bounce can also give our agent repeated attempts to reach her destination without having to return to Start. How many bounces an agent will receive can be adjusted for each agent and activity.

Keep in mind that the destination is not guaranteed. Meaning, we do not know that the agent will reach her destination. The net doesn’t take her to her destination, just back to the same stopping point (s) on the wire. At that point, numerous things could happen to our agent. She could stop again anywhere along the wire. She could give up. She could decide to do something else and return to Start. But, if she tries again and fails, we can adjust the net so that it will catch her and return her to the activity quickly so she can, if she so chooses, keep trying.

Of course, there is still some loss not captured by our allegorical net.

As any of us know who have tried to reach a goal, something is lost with each attempt and repeated attempt – time, energy, confidence, and something economists like to call “opportunity cost,” which is the loss of potential gain from alternative activities when one alternative is chosen.

A good example of opportunity cost can be seen when someone decides to purchase an existing retail store. By choosing one store, we may forego other alternatives like a web-based store or creating our own retail store, either of which could result in financial gain equal to or greater than purchasing the existing store.

So, to put it in mathematical terms, try as we might, while we can minimize loss (l) and encourage activity, we cannot completely eliminate loss with our safety net even if we allow for bounce. Even if we return our agent to the wire almost instantaneously, she will still have loss, if only because of time. So, loss (l) must always be greater and not equal to zero.

But that’s OK, in our allegory, we only need to reduce enough loss to encourage activity. We want our agents to try and, when they fail in their attempts, to be captured by our safety net and return to the activity so they can keep trying to reach their respective destinations.

Or, in other words, sometimes we want to encourage activity without guaranteeing the outcome.

Take the example of owning a home. Society could agree that the destination of home ownership is of such value in our economy that we want more people to accept the risk and engage in the activity of purchasing a home without actually guaranteeing the outcome. Or, in other words, while we want people to try to purchase a home, we don’t just want to give a home to everyone.

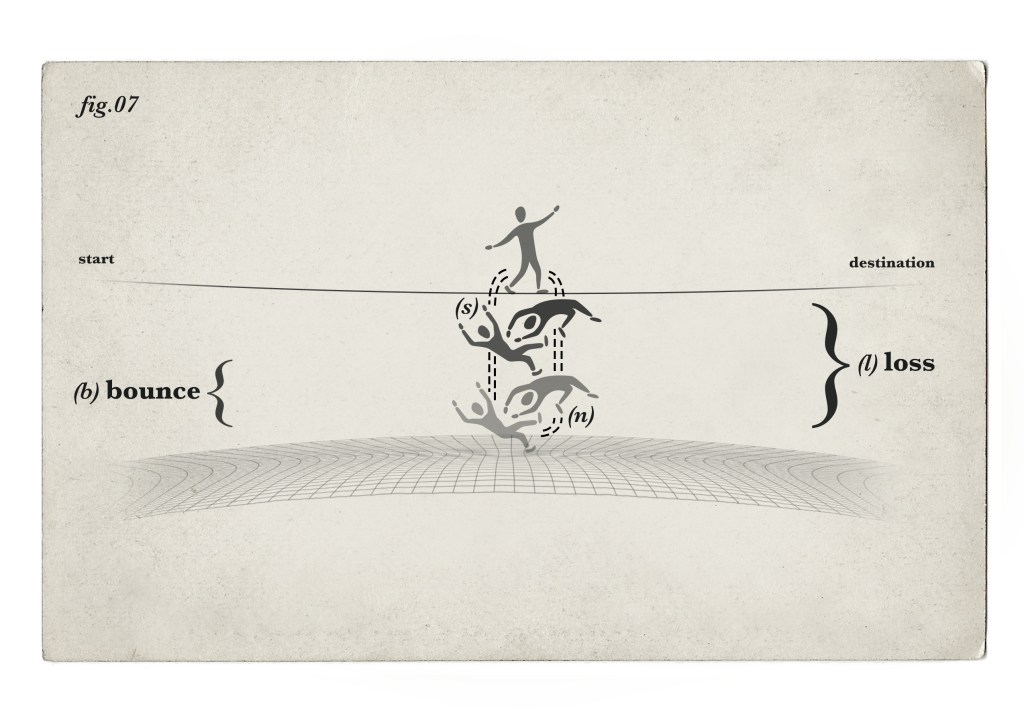

In these cases, we would want the safety net at just the right height and at just the right tension to have enough bounce to return agents to the activity even if they fail multiple times (See Figure 7).

We know that agents will lose time, energy, and other opportunities, so we are going to give the net enough bounce to minimize losses, so agents don’t give up easily. How much bounce we have to give will depend upon the agent.

One problem.

All destinations are not home ownership. In fact, some destinations in our economy clearly aren’t. For these destinations, we may not need or want to minimize the risk of loss otherwise everyone will engage in the activity

Or, to put it in mathematical terms, we don’t want l anywhere close to zero.

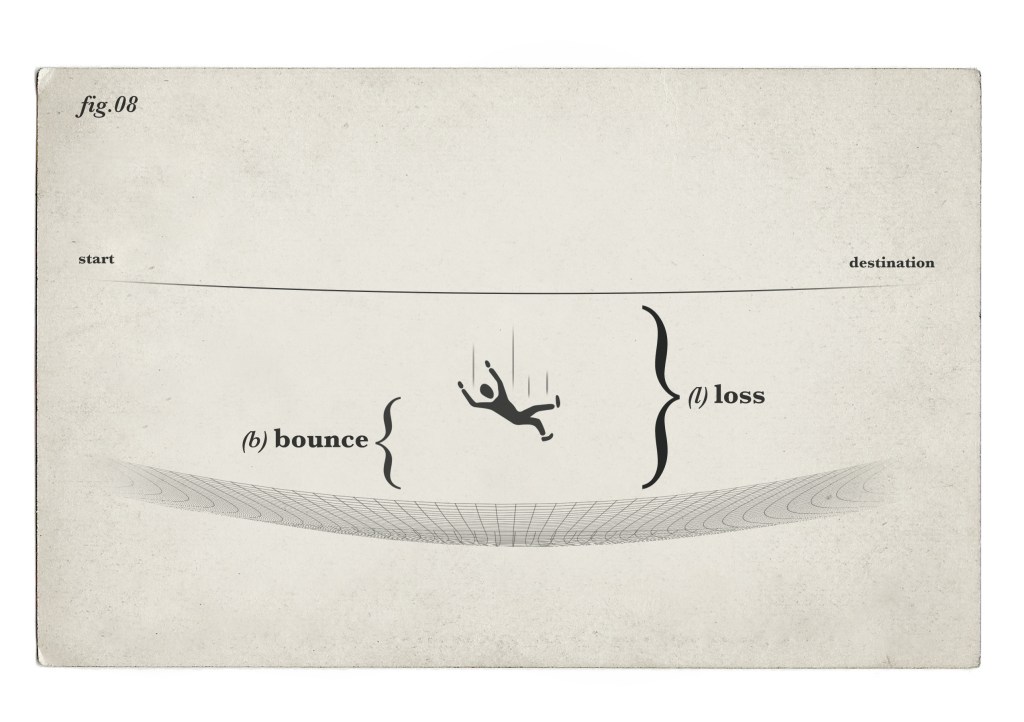

An example of this could be day trading on the stock market. We may not want or need everyone to engage in day trading, so the safety net for it could be set very low (see Figure 8)

In these cases, we are either comfortable with people taking losses or we do not want people to return as quickly or as easily to the activity when a loss is taken.

Very good. Our allegory now gives us the option to mitigate loss and bestow multiple attempts to our agents without guaranteeing outcomes.

Now we’re done, correct?

No, not entirely. We’ve forgotten something. We mentioned it earlier when we talked about our agent lowering his or herself to the ground.

The Floor

It is possible that society may decide that some destinations, like a place to live, are ones we want everyone to reach. We don’t want our agents to merely engage in activities that may lead them to the destination, we want them to reach the destination without suffering loss.

However, as we have shown, our allegorical net is not going to work in these cases, because as we said earlier, we cannot guarantee outcomes, let alone completely eliminate loss, with our Safety Net Allegory. In our allegory, agents can fall from the wire. Success is not guaranteed.

But what if we want everyone to have some minimal standard (for example, a place to live) but still encourage people to take a risk of loss and move forward towards a higher destination of a nicer place to live without actually guaranteeing it? Can we still do that?

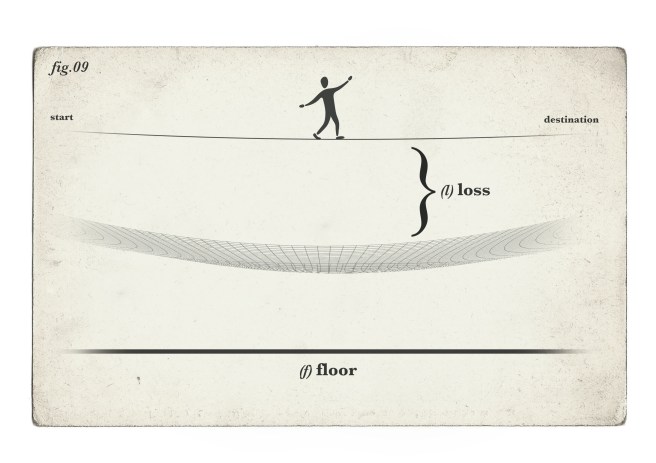

The answer is yes, we can. We do this by putting in a floor (f) (see Figure 9).

If we want our agent to move forward towards the destination of a nicer home, we put in a net. Without the net, she may not accept the risk and move forward. We don’t want to put the net too high or give it too much bounce, otherwise, we risk reducing the loss too much and everyone gets the nicer home.

So, depending upon whether we want to minimize the loss to encourage this economic activity or reward repeated attempts, we either lower the net (n) or adjust the net’s bounce (b).

However, even if she fails in reaching this goal, we want her to have some place to live, so we put in a floor. How far we raise or lower the floor will depend upon what type of home we want her (and everyone else) to have.

But putting in a floor raises another question -what raises or lowers it? Don’t worry, our economy and our allegory both have an answer. It is called a benefit.

Benefits

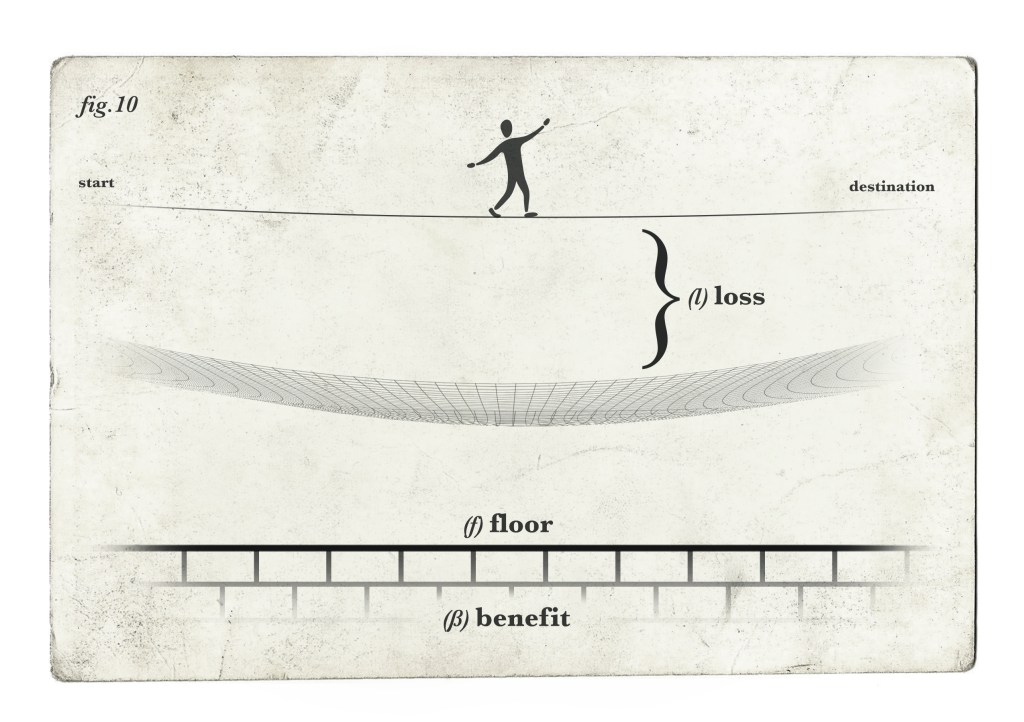

Some people think of benefits as something only employees or people of a certain age receive. But benefits come in many forms from many sources, both public and private, and can be given to anyone at any socioeconomic level. For our allegory, it doesn’t matter what the benefit (b) is or where it came from, we only need to know that it is something that has been determined that everyone should have and as such, raises the floor (see Figure 10).

So, are we done with our Safety Net Allegory? We have accounted for economic activity, a way to measure and limit loss, a way to encourage attempts, and a way to establish a standard of living at or above which we want everyone to live.

Not quite. In fact, we are still missing one very important piece.

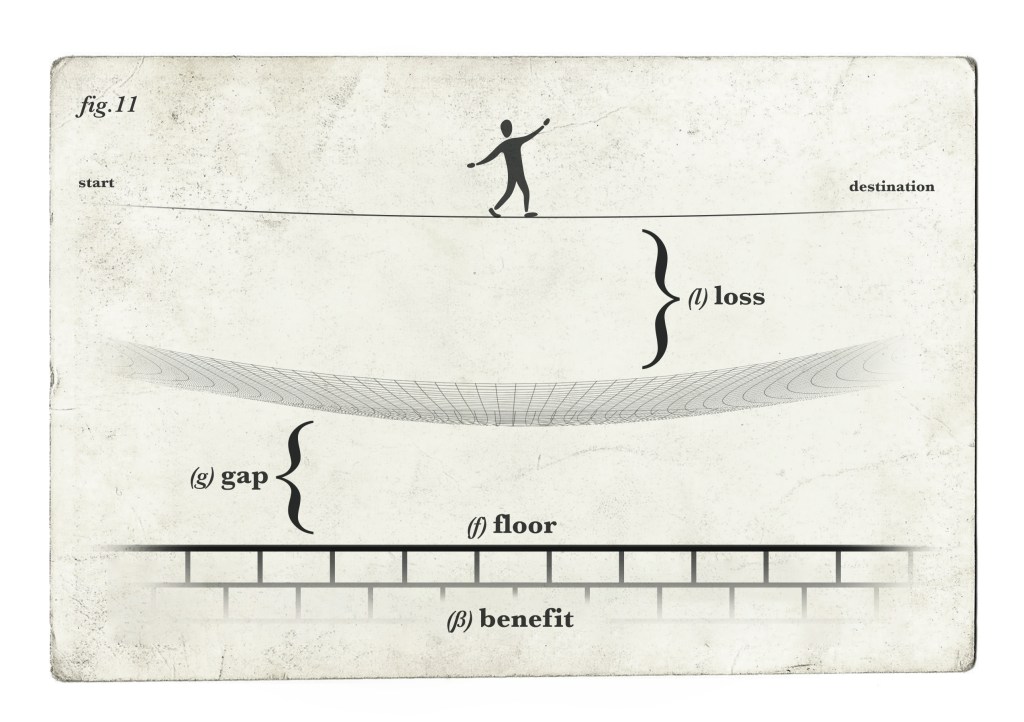

Let’s take a close look at Figure 11.

One thing we notice in this picture is that there is a gap (g) between the floor and the net that is undefined. This gap is the difference, if any, between what society determines everyone should have and the level of acceptable loss which we believe we need to set to encourage people to move forward towards a desired destination without guaranteeing outcomes.

If you raise the floor to meet the net, then you are giving more benefits, which you may not be able to afford or necessarily want or need to give to encourage activity.

If you reduce benefits and lower the floor too far below the net, you are increasing the loss that someone will receive if they do not bounce and/or are unable to return to the wire. An agent may not be able to return to the wire either because our net or our bounce is too low or because, even with repeated attempts, a particular agent is just unsuccessful.

But most importantly, if there is no way to bridge this gap, then some agents cannot reach Start to engage in the desired activity. They just stand on the floor with the net and the wire out of reach.

So, we need a way to close the gap.

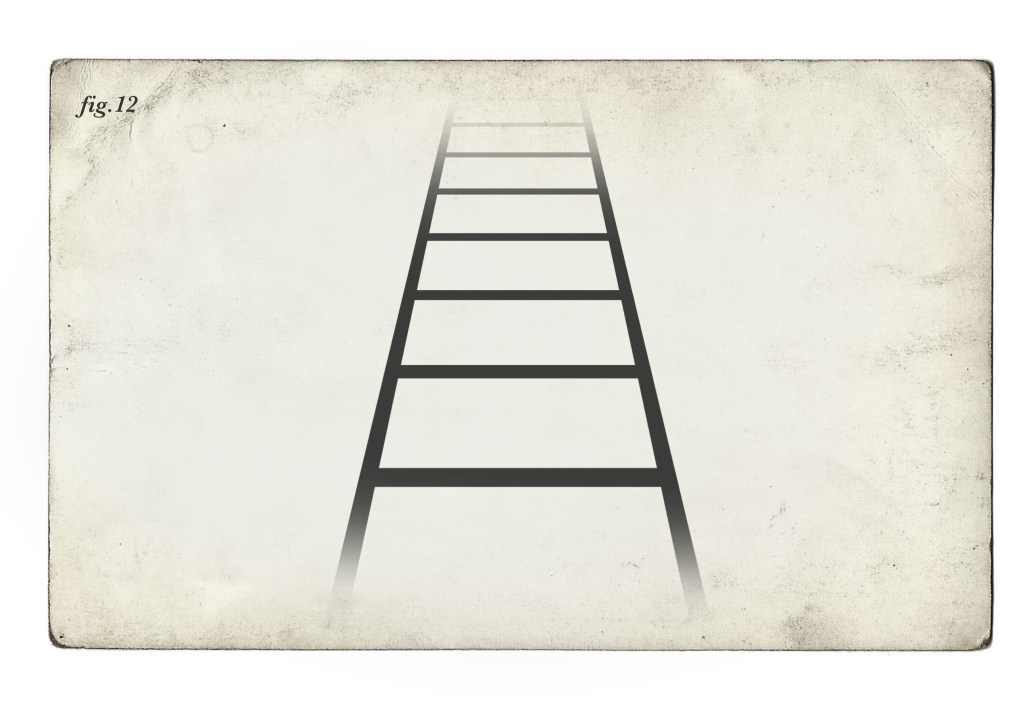

In the high wire artist performance world, this gap is often bridged by a ladder. For our allegorical purposes, this is the ladder needed to get from the floor up to a potential starting place. You’ve heard of this ladder before.

It is called the “ladder of opportunity.”

The Ladder of Opportunity

The ladder of opportunity (see Figure 12) is a very common metaphor. It is used often in literature to describe a person’s ability to rise through economic classes, a claim that is often in dispute.

In our allegory, however, we are not going to use the ladder of opportunity to move someone to a higher economic class. Rather, we use it only to reach a particular starting point from which to reach a particular destination. However, even in our allegory, ladders of opportunity will still be a source of dispute.

Some readers will believe the gap between a failed attempt and starting over is too large. Or, in other words, the ladder needed to reach a particular starting point is too high. Other readers may believe that benefits have risen the floor to a point where the ladder is too short and a desired activity is neither properly encouraged nor rewarded. Finally, some readers may believe the ladder itself, is broken, is not available to everyone, or is just too difficult to climb.

Fortunately, we do not need to resolve this dispute right now. For our allegory to work, we only know that we need a ladder. There has to be a way for people to get to a particular starting point, otherwise, two things can happen.

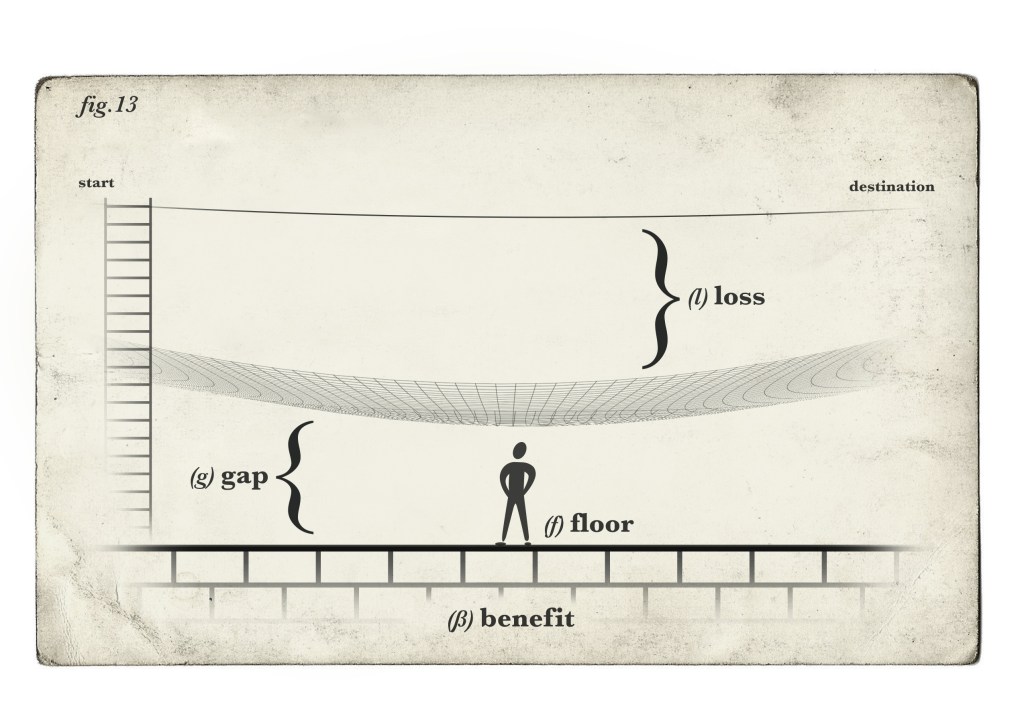

First, some people will be stuck at the floor (see Figure 13).

Second, and equally important, the number of agents who are able to reach a particular destination will be limited.

Let’s go back to the very beginning of our allegory (Figure 1).

To recap, we began our allegory with an agent at Start. We told you that while there are multiple starting points, each higher or lower than the other, to reach a particular destination in our allegory means you have to begin at a starting point.

But how did our agent get there? What put him/her in a position in which to engage in that economic activity in the first place?

For our allegory to work, we need an answer to this question. If we want our agent to engage in a particular economic activity, there has to be a way for that agent to get to that starting point – the point where they can begin their quest towards our desired destination.

Or in other words, for economic activities in which we want everyone to have an opportunity to engage, we need a way for an agent to reach the point at which they can begin to assume the risk of loss, engage in that activity, and reach their destination.

This is not to say that everyone will reach any starting point or any destination. Remember, we are not talking about raising the floor to meet the net or the wire. Rather, we only want a ladder tall enough such that any agent could reach it.

Or in other words, we need a ladder of opportunity so that any agent could assume the risk we want him/her to take to engage in any activity that our economy determines is desirable.

How tall of a ladder our agent will need depends upon where we set our net (n) and our floor (f), or, in other words, the size of the gap (g). The higher the floor is set by our system of benefits, the smaller the gap becomes and the need for a taller ladder decreases.

Ladders can be different. They can be short and easy to climb, or tall and difficult to climb. They can be made available to everyone at low or no cost, or more difficult to find or obtain to increase their value. Climbing the ladder is not guaranteed and comes with its own risk.

A good example of a ladder is knowledge or a skill. Most, if not all, of the value that comes with having knowledge or a skill is in the opportunities that it brings to you. Or, in other words, like a ladder, knowledge allows our agent to reach different starting points in the economy and begin the path towards a destination.

In our economy, some people will have more and taller ladders than others and as such, can engage in more or repeated activities. Reasonable people could disagree about the number and size of the ladders and/or their availability.

But we should agree on the following:

- the ladders need to exist for our agents to have faith in our economy. Faith is important because without it, our agents may demand a different, undesired alternative.

- the ladders need to exist to maintain a sufficient number of agents to participate in certain activities at all levels in the economy. Otherwise, you are limited by the agents who have already reached the starting point, are not deterred by risk, and can engage and remain active.

- our agents need to be sufficiently educated on how our economy works so that they know the ladder exists and how to climb it; and

- our agents need access to whatever physical or mental abilities are needed to be able to climb the ladder.

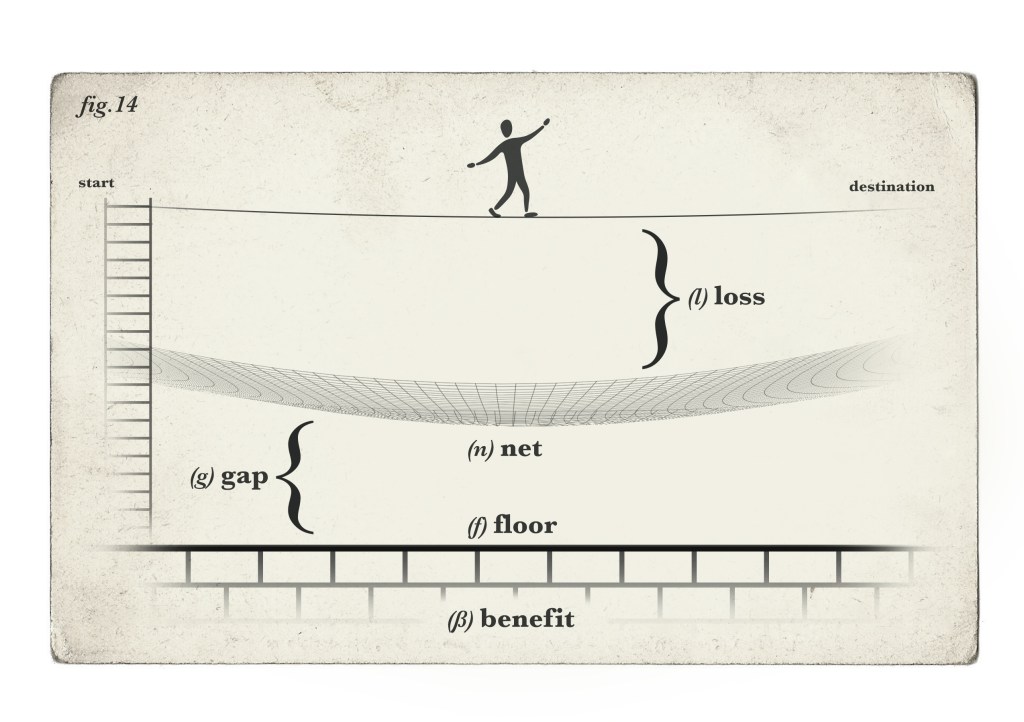

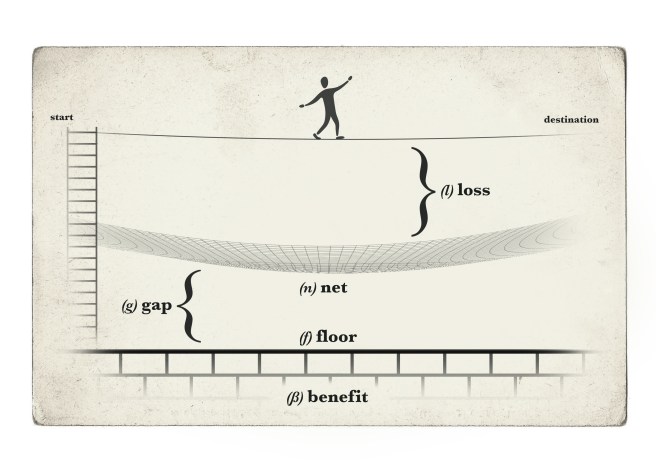

By looking at the final figure in our Allegory (see Figure 14), we can see all of the ways that we can make adjustments in our economy through the use of a safety net.

If we want to encourage the agent in our allegory to engage (or disengage) in any particular economic activity, we can do this by:

- raising or lowering the net (n);

- increasing or decreasing the net’s bounce (b),

- raising or lowering the floor (f) by adding or subtracting benefits (b); and

- providing a ladder to bridge the gap (g).

So, with all of the pieces of our Safety Net Allegory in place, what have we learned and what conclusions could we draw?

Posit

If the Safety Net Allegory is correct, then you could make three assumptions.

First, we could use different nets for different economic activities. Similar to areas of our economy that require continuous adjustments to influence activity (like interest rates and income tax deductions) a net that can be adjusted for height and bounce could give our economy a tool by which we can not only maintain, but encourage and discourage specific economic activity, especially for those destinations that are difficult to reach and/or require multiple attempts.

Second, we could use floors. A floor gives us another tool by which we can maintain and encourage activity in the marketplace, especially for those activities for which losses cannot be easily mitigated or when a particular loss is unacceptable. Floors also save time. By ensuring that everyone can reach a particular destination, it frees time for agents to pursue new ones.

Third, we could use ladders of opportunity. We need ladders so that people can assume the risk we want them to take to reach a destination that our economy determines is desirable. We need to make many different ladders available so that everyone has an opportunity to reach different starting points and different destinations. This is not only important if we want to maintain faith in and support for our economic system, but necessary to maintain activity in sectors of the economy where there are not enough agents.

In closing, we need the ability to adjust all of the parts of our safety net based on the need to encourage activity and the likelihood of reaching a particular destination. This includes:

- the placement of the net and its bounce,

- where we position our floor,

- and how many ladders we are going to make available.

In future stories, we will discuss how this could be done.

Images by Shawn Tarr